The linear character of our time is surely its characteristic feature.

The swiftness, meaning the shortest connection between two points,

can only be represented linearly.

The conquest of earth and of space is achieved in straight line.

Emil Ruder

the line

われわれの時代にみられる線的な性格は、

この時代のきわだった特質である。

速さとはつまり2つの点の間の最短の結合だが、

それはただ線的にのみ表される。

土地と空間の専有は、ただ直線によってのみなされる。

エミール・ルーダー

線

[wide]

[/wide]

[/wide]

In typography there is only one line, the printer’s rule, rigid and straight.

There is no shortage of attempts to free this rigidity: rules with curved corners,

swelled rules, rules developed from pen strokes or from the etching process and many others too.

Such attempts to break away from the rigidity of the rule are detrimental to the purity of typography.

ln the field of type a clear system of measurement exists, in which the sizes are graded in clear proportions.

Good typography is never vague and wistful, and an exuberance of feeling is in no way conducive to it.

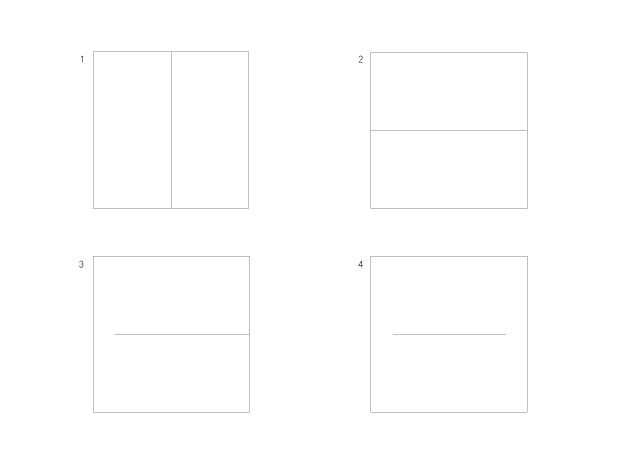

The vertical rule (1) is taut; a tugging takes place outside of the visible area where the rule is taut.

It would be enough to fix the rule at the top and to hang a weight at its bottom,

just there, where the rule lies in its vertical position.

The horizontal rule (2) is quite a bit tauter. lt gains nothing from a direction of fall. lt needs energy to stretch it from left and right.

This rule can never rest, it is constantly reliant on perpetual energy, on the power which stretches it.

A relaxation of tension would allow the rule to roll into a resting position.

With the rule in (3) the starting point is visible. lt is more obvious and contains a direction of movement.

lt begins at the left and moves to the right.

The horizontal rule in (4), restricted left and right, is observable along

its whole extension. However, the rule has lost out on movement, it is undecided as to which direction it should move in.

Helmut Schmid has wonderfully restructured the article in the idea 352 based on the article to be published in the January 1958 issue of “Typografische Monatsblatter” by Emil Ruder. So, we highly recommended that to be read the idea 352 thoroughly. And then you can get a deep understanding of this article.

タイポグラフィにおいて、我々は厳格な、ぴんと張った線のみを知っている。すなわち罫線だ。こうした厳格さを緩め、ほぐそうとするような試みは様々にある。

角を丸くした線、強弱のある線(いわゆるイングリッシュ・ライン)、ペンの筆致や銅版画の技術から発達した罫線など、たくさんある。

だが、罫線(rule) の厳格さから脱しようとするこうした試みは、純粋なタイポグラフィにとっては有害である。 活字の領域では、明晰な度量システムが支配しており、 明快な関係の中でサイズが等級づけられ、分類される。タイポグラフィが、無規定で夢見心地なものであることは決してないし、感情の横溢は全くもって益するところがない。

垂直な罫(1)がぴんと張られている。見える範囲の外で、線は張り詰められているのだ。

まさにここで、線が垂直に横たわるところで、それを上に固定し、取り付けるのには十分なのだ。

水平な罫(2) は、より本質的な意味で緊張している。この罫は、落下方向からは何の作用もない。それは左右 からのエネルギーによつてぴんと張られなければならない。この罫は決して休むことができず、永続的なエネルギーに、自らを張りつめる力に、依存している。緊張が緩めば、罫はたちどころに静止位置へと丸まってしまうだろう。

(3) の水平な罫においては、始まりが見えている。この罫はより明快に、動きの方向を獲得している。これは 左側から始まり、右に向かって動くのだ。

左右が限られた (4) の水平罫では、延長の全体を 見渡すことができる。これによってこの罫はしかし、動きを失う。それはどちらの方向へと向けばいいのか、決めかねている。

このコンテンツはTypografische Monatsblatterの1958 1月号に掲載されたEmil Ruder氏の寄稿記事をHelmut Schmid氏が40年以上の歳月を要し、idea 352の中で編集、デザイン、紹介されたものを一部引用したものです。

次のことをお勧めします、もしあなたがidea 352を熟読すると、このコンテンツを表面的なレベルより深く理解することができます。